Those who once walked these lands in freedom,

were chained, yet stood unbroken.

To their strength, which carried through the storms of slavery

and birthed William Henry Marlin,

who planted a seed of hope on Succour’s soil.

May his descendants continue his vision —

tending these hills with courage,

and sowing a harvest of dignity, justice, and peace.

— Cee Marlin, founder Stichting Marlin Yard

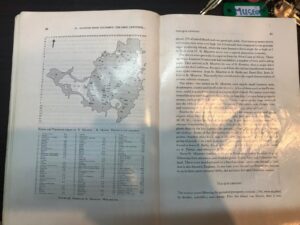

Long before the name Marlin was carved into the soil of Sint Maarten, there lay a stretch of fertile, rolling land known as Succour — Estates 96 and 98 on the old maps, nicknamed “The Golden Rock” by planters who prized its rich volcanic earth. Sprawling across what we now call the southeastern quadrant of the island, Plantation Succour was likely between 50 and 100 hectares (125–250 acres) — a mid-sized estate by Caribbean standards, yet large enough to carve out a grim profit from sugar cane, cotton, tobacco, and guinea corn.

These fields, terraced by calloused hands and bordered by the slave walls still standing in parts today, told stories of endurance. Dry-stacked stone fences divided plots, guided livestock, and marked boundaries laid down by Dutch colonial surveys. These walls were built by enslaved men, women, and children — some captured from West Africa, others born into bondage on Sint Maarten — who cleared the land of stones, piled them into borders, and planted the estate’s first rows of cane and cotton.

The West Indische Compagnie (Dutch West India Company) oversaw the island’s transformation into a plantation economy, funneling African captives to estates like Succour. Though never among the largest sugar exporters, Succour played its role in the brutal machine of Caribbean commerce. Here, cane was cut by hand with machetes under the sweltering sun, sap crushed in mills, and juice boiled in cauldrons to produce raw sugar shipped to Europe. Cotton bolls were plucked from thorny bushes, seeds separated with wooden gins, and fibers spun for trade. Indigo plants, harvested for their precious blue dye, and guinea corn, ground into flour for porridge, lined fields framed by rugged hills.

But the soil of Succour bore more than crops: it bore witness to pain, resistance, and — eventually — reclamation.

In the wake of emancipation in 1863, Succour began changing hands, fragmenting as heirs and creditors traded or inherited parcels. By the late 19th century, a local man named William Henry Marlin, born circa 1857, stepped onto the estate — not as an enslaved worker, but as an emerging landholder. William Henry was a skilled chariot driver (chauffeur) — one of the first Afro-Caribbean men on the island to earn his living navigating horse-drawn carriages across rocky roads. His reputation for steady hands and quick wits brought him work from both merchants and planters.

Through diligence, luck, and a measure of justice long denied to his forebears, William Henry Marlin acquired lands at Succour. The old plantation that once enslaved his people became the Marlin Estate, held in trust by a family that knew both the sting of oppression and the power of freedom.

William Henry’s marriage in 1901 to Marguerita Eliza Joe, daughter of Laurent Joe and Ellen Arrindell, cemented the Marlin family’s place among the landholding families of Sint Maarten. Their children — including Victoria Madelaine Marlin, who would become known as Grandma Vicky — grew up among Succour’s ridges, playing in the shadow of stone walls their ancestors had built, tending goats and small fields, and watching the sugar and cotton fade as times changed.

It was Victoria Madelaine Marlin, who gave the surrounding area its name: The Keys. She earned the nickname because she carried many keys to homes she cleaned, cared for, or looked after, each key a symbol of trust earned through her dedication to her community. Over time, “The Keys” became the name of the village itself — a place of kinship, where the descendants of Succour’s fields found belonging.

Victoria’s son, Louis Lorenzo Marlin, carried forward her strength and pride in the family’s land, raising his daughter Marcilia Victoria Marlin with the same determination. Marcilia worked tirelessly to help develop The Keys, bringing running water and electricity to the area and transforming it from a sleepy settlement into a vibrant neighborhood where families could thrive with dignity and opportunity.

In the new generation, Cee Marlin, great-grandson of William Henry, grandson of Victoria, and son of Marcilia, determined to honor his ancestors by continuing their work. In the heart of The Keys, he founded Vicky’s Keys — the first eco hostel and volunteer center on Sint Maarten — as a living tribute to the women who shaped his path. Here, volunteers from around the world have stayed to help build sustainable projects, plant gardens, and strengthen community ties. From this center, he launched the Marlin Yard Foundation during the COVID-19 pandemic, answering a new call to help Sint Maarten achieve food security in the face of hurricanes like Irma in 2017 and the unprecedented crisis of 2020.

Today, the remnants of Plantation Succour’s original lands can be traced from Madame Estate, near Philipsburg’s eastern entrance, along Sucker Garden Road, into the heart of The Keys village, and eastward toward the ridges climbing to Guana Bay Road — brushing the hills above Point Blanche. These are the modern landscapes where stone slave walls still lie hidden beneath brush, where goats graze among ancient borders, and where new community gardens promise a future rooted in justice.

With plans for the Roots Revival Project opening historic hiking trails through Succour’s hills and the FFG Community Garden replanting crops on this sacred ground, the story of Succour is no longer one of sorrow alone. It is a story of return, renewal, and resilience — where the fields once watered by tears now grow hope, and the land remembers the names of those who reclaimed it.

The year 2020 brought new challenges to Sint Maarten. As COVID-19 shuttered borders and Hurricane Irma’s scars still marked the landscape, Cee Marlin stood among the ancient stone walls of Plantation Succour and envisioned something revolutionary: Food Farm Gardens St. Maarten (FFG) — a project that would transform his family’s ancestral land from a symbol of colonial exploitation into the Caribbean’s premier hub of food sovereignty.

Where sugar cane once grew under the whip, community gardens now flourish under community care. The same fertile volcanic soil that enriched Dutch planters for centuries now feeds 400+ Sint Maarten families through FFG’s Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) program. The 300+ year-old slave walls that once divided plantation plots now frame individual garden allotments where families grow callaloo, sweet potatoes, and traditional Caribbean crops alongside hurricane-resistant vegetables.

FFG’s mission is both simple and profound: to prove that small islands can achieve big agricultural impact through community collaboration and sustainable innovation. Using cutting-edge Cooling House technology, the project is destined to produce 324,000 kg of organic vegetables annually — enough to feed hundreds of families while creating a model for Caribbean food security that can weather any storm.

The transformation goes beyond agriculture. Through the Heritage Agrarian Institute of Caribbean Innovation (HAICI), Plantation Succour will become a living classroom where traditional Caribbean farming wisdom meets modern sustainable practices. Students from across the region learn aquaponics, permaculture, and climate-resilient agriculture on the same land where their ancestors once labored without choice.

Every plot rented, every vegetable harvested, every student trained represents a victory over the plantation system. Where enslaved workers once had no stake in their labor’s fruits, FFG’s Crowd Profit Sharing model ensures community members become stakeholders in their food system’s success. The Caribbean Eco Token (CARET) gives residents a voice in farm management decisions, transforming colonial hierarchy into democratic governance.

The stone walls still stand — not as barriers, but as bridges between past and future. They remind every visitor that this land remembers both its pain and its power. They frame gardens where children learn to grow food their great-grandparents could only dream of owning. They anchor a project that proves the most powerful form of resistance is not destruction, but transformation.

From the ashes of Hurricane Irma and the isolation of COVID-19, FFG emerged as proof that crisis can catalyze community. What began as emergency food security has evolved into a comprehensive model for Caribbean agricultural independence. The same soil that once exported wealth to Europe now grows wealth for Sint Maarten families.

Today, when visitors walk through FFG’s community gardens, they walk through living history. They see how the Marlin family’s century-long journey from enslavement to land ownership continues through Cee’s vision of food sovereignty. They witness how colonial infrastructure can be repurposed for community empowerment. They experience how heritage preservation and agricultural innovation can flourish together.

The story of Plantation Succour is no longer just about what was taken — it’s about what’s being reclaimed. Through Food Farm Gardens, the land that once symbolized exploitation now represents empowerment. The fields that once grew crops for distant markets now grow food for local families. The walls that once divided enslaved from free now unite a community in the shared work of feeding themselves.

This is the harvest of justice: seeds planted in ancestral soil, tended by free hands, and shared among neighbors who understand that true wealth grows from the ground up.